1. Capitalist restructuring in the SYRIZA-ANEL times

At the time of writing of this text, we are in the third year of the SYRIZA-ANEL coalition government. After the polarized days of the 2015 referendum, the period that followed the Greek government has normalized many of the rupture points it supposedly had with the “institutions” 1 and became a submissive student without causing considerable reactions domestically, at least so far. The awkwardness and disillusionment, or feeling of outright betrayal for some of the former followers that believed in the “first ever left-wing government in Greece”, looks to be the main social outcome of the government that came to power promising a secure exit from the Greek debt crisis and an end to austerity. In our analysis 32, the failure of the previous cycle of struggles (roughly between 2008 and 2012) precedes the rise of the SYRIZA-led government. The inability of this cycle of struggles to stop or, at least, raise serious obstacles in the restructuring process gave a stepping-stone to the SYRIZA-ANEL alliance that promised a governmental resolution of these issues. It cannot, however, be summarized in an article, since this would require a wider collective process of reflection and self-criticism.

What can be analysed however, and this is what this text tries to do, is to trace the ways in which the SYRIZA-ANEL government continues the capitalist restructuring that had began during previous governments, to focus on the similarities with previous years and to point the changes that can be seen on the horizon regarding the changing role and function of the state in relation to social control and mediation processes, along with the management of poverty and refugee flows. All these are opportunities used by Tsipras’s administration to pave the way for the circulation of capital but also, to broaden social control. Furthermore, based on what this new government really does and not what it claims to do, we will try to assess the degree of its success to endorse reforms necessary to the bosses, effected on the shifting landscape of social antagonism, as it formed during the last few years.

A. Continuities and (slight) changes of the restructuring policy in the public sector

It was pretty obvious from early on in this “anti-austerity” government that the SYRIZA-ANEL coalition would continue the capitalist restructuring with a broadened consensus and mediate in an effective way most class antagonisms of the earlier period. Varoufakis’s statement that government and lenders “agree to the 70% of the program” shows how these changes are largely compatible with a strategy of neoliberal restructuring. However, in order to restore the gap opened in parliamentary representation, which deepened in the early years of the crisis, it was necessary to change the role of the state in the social formation. When we talk about the state, we do not mean only the government body, state services, or repressive mechanisms. The post-war state in Greece developed its mediating role through a multilayered expansion in society. The main element of this expansion is the fact that the state, largely indentified as the “public” itself, was and remains the largest employer in the country.

It is important, therefore, to initially examine the struggles that unfolded in the public sector during the transition to the SYRIZA-ANEL era as struggles that were given within the confines of a solidified bureaucratic mechanism of mediation. Struggles that were dominated by institutional unions and professional, party-controlled unionists had as primary aim to maintain these traditional forms of mediation and the social networks of power that supported them. Examples of struggles show very clearly the passage from a state-logic of repression of struggles during the earlier coalition government of ND-PASOK-DIMAR, to a “nationalisation” of struggles during the government of SYRIZA-ANEL. Within the framework of “anti-austerity” politics, important struggles turned into campaigns that aimed to the downfall of one government and its substitution with another. One after the other, struggles were baptized into the “mother of all battles” that were to end austerity by bringing the anti-austerity forces to government. This resulted in an excessive exaggeration of political ideological discourses, and concurrently absolutely no concern on the everyday practical issues that would make this particular struggle achieve its aims. For example, during the strike of the Athens underground rail (Metro) workers, a practical question was posed in a striking workers’ assembly: what should be done in case the government proclaims a state of emergency and forces strikers back to work? The answer of unionists, up to then so fiery with revolutionary rhetorics, was to summarily shut down the discussion. A similar disengagement happened during the shutdown of the public broadcasting company (ERT) by the previous govenrment, when the real question of coordinating the personnel strike with private sector media employees and the equal participation of those who expressed their solidarity was posed. The immediate issues of workers’ organization were considered to be of no particular importance in the face of political slogans of reopening the channels and thus “restoring democracy”; essentially, in other words, of bringing to power an “anti-austerity government”.

Within the premises of struggles given in the public sector, burning issues such as the safeguarding of the struggle, the different needs and also the different salary scales of workers striking in common, and questions of how to widen the scope of struggles to include other potential subjects, were very little discussed, if not actively avoided. In their place was put a festive – bordering on kitsch – political spectacle that anticipated the upcoming SYRIZA government as the ultimate arbitrator of class antagonism. Given the entrenched regime of clientelistic and paternalistic practices in the public sector, these politics represented a clear-cut strategy of SYRIZA to solidify its power in strategic sectors of the public sector, promising, in return, the reopening of public broadcasting television channels, the re-hiring of municipal workers, the nationalization of the public electricity company, etc. This, however, had a further significant impact: from the struggles that took place, none of them managed to remove class divisions within the workplace. So, beyond the spectacle offered, these struggles did nothing more than reproduce established clientelistic practices within the unions and to promote, once again, the state as the mediator of class conflict.

These struggles however had bred a climate of expectation that had no realistic resolution through state politics. In the summer of 2015, SYRIZA-ANEL come face to face with the promises of “anti-austerity” campaigns, and are forced against the wall of intensified threats from foreign lenders; it therefore decides to perform a spectacular dialectical pirouette: It will attempt to preserve and extend the restructuring policies of the previous government in the wider public sector while, at the same time, maintaining it as the privileged ground of state mediation and a pool of potential voters. We have to admit that in this difficult task of restructuring the public sector while maintaining the necessary mediations, Tsipras’s administration did a bit better than the ND-PASOK-DIMAR coalition government had previously. We distinguish three characteristics of the enforced policy:

1. On a general level, public sector restructuring is continued through extensive privatizations of state assets (e.g. ports, railway network, airports). The new coalition government makes a small difference and simultaneously protects the trade unions as mediators by transferring employees to other public companies, like, for example, the logistics sector for the port of Pireaus.

2. Although the public sector continues to be understaffed, the SYRIZA-ANEL administration fully exhausted all possibilities of new recruitments.

3. The coalition government fully expands flexible working relations with fixed-time contracts (with a usual duration of two, eight months) and the usage of “workfare” workers from the Unemployment Service, to cover the needs of the public sector. So in a general level, this government does the same things as the previous ones, but in a more massive scale with the addition of some details that require a thorough examination.

The Greek State always used public funds for party reasons. The SYRIZA-ANEL coalition turns to a more rationalized management that superficially looks fairer. It does not want to replace clientelism but to rationalize its mediation of class struggles. It does not promise permanent employment but aims to sustain the father-figure of the state by offering eight-month-long contracts for the most impoverished unemployed. The government, as any government before it, has as ultimate goal to preserve, if not increase, its voters by offering jobs in the public sector within the new confines of the economic crisis. If, in the past, social consensus was secured through the provision of permanent and stable work in the public sector, it is now tested through the provision of cheap and undervalued work contracts to the long-term unemployed. Meanwhile, it preserves the clientelistic hopes of unemployed/temporary workers through various “classic” means for promising a better and more stable working future. Last year for example, the government gave hopes that five-month workfare contracts may be extended (they never did). Simultaneously, they proceeded to consecutively renew two-month fixed-term contracts in several municipalities by employing loopholes in the draft law of the ministry of employment.

With the massive expansions of flexible working relations in the public sector, we believe that the frame of struggles within it changes also. If struggles in public sector will be given with the terms we already know so far, they won’t concern a lot of people. Alternatively, if they are big enough, they will not be given with the terms we know. For now, a middling situation is preserved where trade unionists represent civil servants and at the same time are also in charge of some struggles of precarious workers in the civil sector, who have expectations of permanent employment.

B. The “humanitarian” management of the crisis: workfare, ΚΕΑ, community centers and recording/discipline of local and immigrant “claimants”

Within the tight confines of the memorandum, SYRIZA-ANEL continue the politics of the previous gonvernments, with the expected results. The “traditional” reproduction forms of the middle class as well as the working class are damaged. A series of measures, such as increased and extended property taxes, increased VAT on basic products, house auctions for debts to the state and the reduction of untaxed income limits, make the reproduction of the very social layers which comprised the government’s electoral base (self-employed and salaried employees) even harder.

The new addition to the palette of neoliberal governance that SYRIZA-ANEL brings seems to be the “humanitarian” management of the crisis. Even after the elections of January 2015, the “humanitarian crisis” was a central doctrine in the strategy of SYRIZA. The notion of a country in the brink of humanitarian crisis was one of the strongest cards in the suit of the government in its negotiations with the Troika, or so the government thought. The logic of this strategy was to reach a recognition that the restructuring has done so much damage to the country that we could speak of an event similar to a massive destruction, and hence an event that has to be treated as such by the state, the NGOs and the creditors. However, especially after their second electoral victory this so-called left-wing management of the crisis looks increasingly more similar to the neoliberal plans for “social economy” as well as the combined politics of “social care” rationalization and obligation to work (for the lowest strata of society).

The measures “against the humanitarian crisis” are nothing else than the continuation of tested neoliberal recipes, mainly regarding the control of proletarianised populations. So here we should make clear – even at the risk of repeating ourselves – that when we talk about humanitarianism, we talk about neoliberal policies affecting the lives of the locals and immigrants in multiple ways.

Wherever a disaster has hit, investment in humanitarian activity is a major tool in the hands of the bosses in order to assure capitalist development.

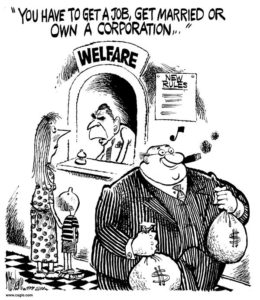

The neoliberal management of the crisis leaves intact the very capitalist assumptions of the problem. The devaluation of our lives through lay-offs, increasing taxes, unemployment etc, is not presented as conscious political choices of the bosses and the state but as procedures of a natural destruction in which the state only intervenes to help raise society back on its feet. This purported help is understood as a give and take where the state gives small opportunities and benefits and the claimants of these opportunities give in return hard work and proof of being disciplined. To put it more simply: for a person who gets the sack, there are fewer, or no benefits at all; familial aspects of his or her social reproduction, such as old age pensions that tricked down to younger family members are also cut. To these persons, a “humanitarian” benefit is offered (called KEA – Social Solidarity Income)3. But this is by no means free: the recipient is now a claimant who needs to accept all offered jobs and training seminars by the unemployment office and unannounced checks by unemployment office personnel in his place of residence. The “humanitarian” benefits are always accompanied by controls and studies, digital unification of the control systems and worsening of work conditions and salaries.

Something new here is what is called “community centres”. The government intends to open such centres in neighbourhoods with high unemployment rates, in order to control unemployment programs and benefits and promote voluntary work. We consider that behind this strategy lies an intention to integrate local solidarity structures that were part of the movement and turn their experience into an official part of the current policies.

The attitudes of current or potential claimants towards the “opportunity” offered will be evaluated on an individual level by state agencies. This way, the claimants will be divided to those who are worthy of benefits or “normal” waged labour and those who are unworthy of it and consciously choose their own marginalization. For all its humanitarian posturing and a social-democratic rhetoric on equal opportunities, the state is thus able to assess individually each worker’s or unemployed person’s discipline. At the same time, it forms a mass of cheap, devalued workforce, which is now paid by funds previously used for social benefits, allowing the bosses to alter the existing class composition in their favour.

The humanitarian rhetoric of the early days of the SYRIZA-ANEL government enabled it to keep its left-wing hat of mass politics on, while at the same time pushing the most neo-liberal agenda as far as the work market and the social state is concerned. This government continued the notion of an emergency state, albeit on a different note. While in the previous right-wing inflected governments the basic aspect of this emergency was the control of popular unrest through a zero-tolerance policy, this one employed the “humanitarian management of the crisis” to socially justify and solidify capitalist restructuring. The humanitarian aspect of crisis politics enables this government to pass laws dictated by the memoranda, while creating the illusion that these are temporary measures to alleviate the crisis, which will be taken back when capitalist normality is restored. The left-wing past of this government, as well as its exploitation of the previous cycle of struggles to come to power, enable it to enforce capitalist restructuring without major social unrest, which would necessitate a stricter form of “management”.

It became quite obvious for those who watched the soap opera of “negotiations” carefully that almost every “humanitarian” measure was in accord with the demands that the creditors put forward in order to issue new funds. The funds, in contrast with their past use (for large scale construction, administration, infrastructure), are now directed towards those social policies that lead to work restructuring. The state benefits greatly from the abolition of traditionally provided benefits. But, more importantly, this is a very effective way to ideologically contain the working classes who had until recently the ability to reproduce themselves through family networks of support, and thus a greater ability to oppose capitalist restructuring.

To what the bosses gain we have to add of course the extension of a social economy sector aiming at capital circulation and having as an object the most vulnerable population groups. It is the first time that we see in Greece the formation of an extensive tertiary “humanitarian” service sector. Mass immigration towards Europe gave the bosses an opportunity to control these populations and to clarify the operational status quo of private and state organisms. The so-called “immigration crisis” will surely make some NGO’s stronger while it will let others isolated. The sharing of the pie has begun, with the state being in conflict with mediators regarding the distribution of european funds.

In this fluid scenery, the figure of the claimant is one that probably has a potential to unite parts of the local proletariat and immigrants. This is a figure that, with the sociological goggles of the bosses, comprises a mass that depends on the social provisions and benefits of the state for its survival and reproduction. The aim, in the near future, is to make this mass more visible to the services of the state and record with a degree of accuracy every claimant. This is a move that purportedly leads to a “rationalization” of the state. In this context, however, the impact on lower strata is much larger: the major role of the National Statistics Service in the recording and analysis of the spectrum of precarity, as well as the introduction of digital archiving and the unification of benefit systems leads directly to the social marginalization of lower strata, to a particular class of sub-proletarians open to forced exploitation.

It is in the same context that we place the changes in workfare programs which were applied last year, as a response to the mass struggle of claimants working for municipalities in the end of 2015. The small victories, which for us show the importance of struggles in bringing concrete results, can’t but be accompanied for the state by a deeper incorporation of claimants in the workfare logic. The augmentation of the working period from 5 to 8 months (being a demand of this struggle), which will allow some unemployed to reach unemployment benefits, is made possible through the extension of funding, not by the european pachages but directly by the state which turns a part of the work offered to trainning vouchers. The acqisition of two days leave per month is applied by exception: these days are not presented as an official leave but as “justified absence”. Finally a redistribution of the programs is tried through the examination of unemployment rates in each municipality separatedly. The programs are also partially used in a clientelist way substituting the previous clientelist policy of hiring in the public sector. This way the government tries to reach out to a part of its electoral base. We consider that this government does this more effectively than the previous one, up to the point of writing these lines.

Here we will risk the prediction that workfare will play a major role in the “humanitarian policies” of immigrant integration. In contrast to most European countries where workfare is headed towards immigrant populations and their descendants, in Greece until now workfare is exclusively directed to local proletarians. The ideology of workfare programmes for immigrants will probably ask the latter to prove that they are worthy of papers and benefits by offering low-cost labour to the “kind society that accepts them”4. The collusion between state politics and widespread racist reactions in Greek society is probably best portrayed in the fact that fascists instead of complaining about “jobs taken by immigrants” complain about the money spent to house and feed them, proposing that they should “work for society”.

2. Managing Immigration – the role of NGOs

A landmark for the Syriza-Anel government was the increased influx of immigrants as a result of the wars raging in the Middle East and Africa. This is for the neo–liberal humanitarian newspeak something akin to a natural catastrophe that necessitates a rational form of management. For us, what is nowadays called humanitarian crisis is but another aspect of the management of war on the edges of the so-called civilized world. Besides the geopolitical considerations of this sort of management, we have to take in stock the deepening and expansion of a philosophy of “humanitarian war” – of the humanitarian measures that are applied as an inextricable part of war campaigns of the West. We think this humanitarian machine is part of capitalist restructuring, both in “Third” world countries, but also in the confines of the developed West. We already saw how state humanitarianism is an expansion of the state of emergency in crisis through which neoliberal politics can more safely be passed. When this humanitarianism is directed towards “strangers” from abroad, it meets the everyday and institutional racism in the West to produce deeply devalued exploited populations.

It is important to look at how in this context the state manages “exceptional” events like the increased flows of immigrants. We do not deny the sharp increase in these flows, but we emphasise the exceptionality to point out quite the contrary, that these flows will constitute a permanent major issue for Western states as long as these states increase their military presence globally. On the other hand, we recognize that the Greek state was far from ready to face this influx, dealing already as it where with the sharp increase in public debt. It is easily understandable that, whatever the government coalition in power were, the previous politics of determent and prevention of entry by torture if necessary, had reached its limits already by the end of 2014 – not only because of its barely hidden barbarism, but mainly because it was unable to contain the immigration flows and prevent them from entering Greece. From the moment that this policing failed, the Greek state turned to mama–EU, using the immigration “issue” as a strong card in its negotiations with the European partners. It is indicative that Panos Kammenos, leader of the ANEL part of the government, saw it fit to threaten the partners that “[Greece] is going to fill you with jihadists” in 2015. After the closure of the borders and the EU-Turkey deal in March 2016, we enter a new phase in which the Greek state has to manage, with EU money, tens of thousands of immigrants trapped in hot-spots, and sees the “refugee crisis” as an opportunity for development.

In this context, there are two remarkable new traits that have characterized this new form of management. The first is the relative “tolerance” towards socially instituted refugee housing initiatives from below – which we will discuss further in what follows.5 The second is the active involvement of the private sector in the form of NGOs, which we will analyze presently.

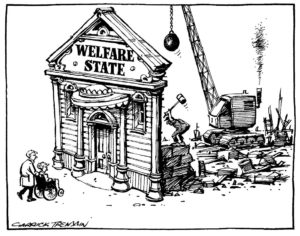

The dissolution of the welfare state in the memorandum era also meant the retreat of the state from large areas of welfare. For some sectors, like mental health, this amounted to wholesale abandonment. This happened through various channels, for example by forcing civil servants of some age to get early pensions or by withdrawing funds for welfare. For some radicals, this was seen as an opportunity for the movement to occupy this space and build its own institutions for welfare and everyday social reproduction. This was done to some degree, but whether the structures set up by the movement really catered for everyday needs – even those of its people – remains to be seen (and mostly because the movement itself refuses to take stock of this experience critically). In fact, however, the state not only retreated from these sectors which it traditionally controlled, but opened them up to private companies, while positioning itself as ultimate arbitrator and coordinator. This is essentially a strategy of transforming areas of welfare into areas of business competition and profit–making; in transforiming it in neo-liberal terms, into areas of “social economy”. The privatization of welfare affects us by further devaluing us as living and workings subjects. But in no way does that means that the crisis–state withdraws from welfare. On the contrary, the management of the “refugee” crisis, of “social economy” and the “humanitarian” politics we see a strategy in the making to broaden state intervention in these fields in favor of capitalist profit making.

This process meant that the NGOs in general solidified their position in areas of welfare that were covered by the state or even social structures and institutions such as familial and friendly networks. NGO presence in Greece is already longer than a decade and they constitute a measurable factor in the development of welfare services. The difficulty of understanding their role in Greece comes from the widespread belief that they are a bunch of embezzlers of public funds. Yet, while there are cases in which some NGOs were set up just for this purpose, most of these acting in Greece right now are multinational organizations that have private funding, a huge payroll, serious resources and a great impact. The “entry point” for most of these organizations has been the various inclusion initiatives for “precarious” groups – mostly immigrants but also long-term unemployed, single parents and women who have suffered domestic violence. 6

In this respect, we can look at the management of the “refugee crisis” as a dress rehearsal for the social economy plan as it will transpire in the future. We do not suggest that Syriza and ANEL approached the issue with ready-made plans. But we can see how a crisis can be used as an opportunity to clarify the relationships of state and private sectors, the role that the institutions play in it and the issue of grassroots participation. The involvement of big NGOs in Greece should also be seen under this light. NGO presence in Greece is not a new phenomenon. In the specific social context, however, it is a way to institutionalize and control volunteer activity, and effectively curtail grassroots solidarity. For example, in the first few months, doctors who wanted to offer volunteer service could by law only do so through NGOs. At the same time, this is a great opportunity for the state to clear out the field of non-governmental involvement in favour of big and well-funded international NGOs against smaller local-based ones. As part of this effort, the state-led propaganda against some supposedly irresponsible and rogue elements (read: people in solidarity outside NGOs) targeted smaller and not state-supervised initiatives, especially in the islands of the eastern Aegean sea during the fall of 2015.

Any analysis of social economy as it is laid out by the state, institutions and companies, should not run its gamut in the commonly held belief that NGOs are but profiteering schemes that embezzle European Funding. The latter should be seen more generally as forms of expanding wage–based exploitation as part of the restructuring of social welfare in Greece – and perhaps elsewhere. We would like here to highlight two points in this process that are interesting to us: first, the way that relationships of exploitation are solidified through commonly-held ideologies about NGO workers and service workers in general. Second, the change in the model of population management, especially regarding immigrants – that typically constitute the lower strata. This second point raises for us questions about the relationships between service workers and users, and opens up the potential for common struggle.

For us, NGOs reflect the fragmentation of “traditionally” state-operated welfare services in a post-fordist economy. Within the largest NGOs there is a variety of jobs and work relations, as in every developed sector of capitalist economy. There are many well paid positions with full worker’s rights, but without the permanence and the syndicalist force of civil servants. The general rule is fixed-term contracts and a certain flexibility in working conditions, which is justified by a business philosophy of “giving” to one’s fellow human being. In large NGOs, there have even been day–long contracts. When there are contracts, the salaries and payment dates are tied to the programs that fund the NGO. So for the workers in those companies, the pressure is even larger to attain the goals of the program – and secure funding-, and treat bosses with some deference. High percentages of unemployment in social science and humanities degree holders creates an opportunity for bosses, who can easily replace resisting workers with others, without much consequence for them or the job undertaken. The humanitarian ideology backing it all up also becomes a lever for exploitation for workers at NGOs, since this can be brought up as an excuse for late payments, unpaid overtime in “special” occasions, “flexibility” in employment rights, etc.

For part of the anti–authoritarian/anarchist/autonomous milieu, the change in the management model for immigrant flows has created a visible bewilderment. Most of the efforts made is to read this change as a continuation of the ideology of new totalitarianism and contemporary fascism – for this reason, they denounce NGOs as part of the modern military-industrial complex. The overriding emphasis on this part of the equation is for us problematic, because, to begin with, it underestimates the state functions that aim towards the social reproduction of the workforce and are currently under restructuring. To deny that the military-industrial complex and western imperialism is the root cause of the immigrant flows from Asia and Africa, would be absurd, and we are not going to do so.7 Neither will we deny that the management of these flows and their submission into a “surplus” workforce within national states in the West is today common truth. NGOs play a significant role in recording and sorting out immigrants into refugees-asylum seekers and “illegal immigrants” to be deported. However, any analysis on the question of immigration cannot stop in this over-simplifying point. Immigrants may be without papers, but they have a voice to tell their stories, they have bodies to fight against restrictions in their movement, and, above all, they have basic needs that need to be fulfilled, like all of us. Their social and material reproduction is a big issue for the state, but not, as it seems, for the aforementioned analyses. For us, NGOs are significant players in the implementation of state politics, but furthermore they are instrumental in providing welfare assistance to immigrants. If we treat them merely as embezzlers of EU funds, or simply as agents of the new totalitarianism, we overlook the big picture of capitalist restructuring of welfare politics – a generalized attack on the existence and reproduction of local and immigrant exploited populations.

We do not approach workers in NGOs as “humanitarian cops”, but we understand them as workers in the field of state welfare, that has been ceded to the private sector and NGOs.8 We see in their working position the prospect of new fields of struggle that can embody the experience of previous circles of contestation and attempt to link the often politicised exploited workers in the new social economy with the immigrant users of these services – in order to strengthen the struggles of the latter. But we will come back to this in what follows.

3. Some early conclusions regarding the changes in state policy and the prospects of struggle against it

One basic question regarding the restructuring of the state during the SYRIZA-ANEL times is whether the changes have a temporary character or are more permanent. Are they the continuum of a strategic capitalist restructuring that will continue from the next in the line of succession or are they temporary experimentations of the “sorcerer’s apprentices” of the Left with resources available from European funding, before the return to a hard neoliberal line? Can we talk of the emergence of a well-planned “humanitarian state” as an answer of the bosses to capitalist crisis? Or is this an overstated view of confronting some of the crisis’ consequences from a State that has repression as its basic weapon?

The answer we attempt to give starts from three basic assumptions. First, this is not the time to risk predictions and build grand ideological narratives. The capitalist system, the EU, the Greek State are within a historical, long-term crisis that has no exit in sight. A state of emergency and capitalist restructuring akin to class warfare, yet without an adequate answer from the bosses’ side to the withdrawal of political consent o f those from below from numerous goverments, remain the relative and temporary characteristics in this environment. As long as the history of human societies was and is the history of class struggle, we can support that this systemic instability reflects the fluidity and fragmentation of our class. Let us not fool ourselves, this moment makes it obvious that every big “revolutionary” (or at least anti-austerity…) narrative is unable to give sufficient answers to the practical issues of dealing with the crisis, but insists on repeating outdated socialdemocratic rhetorics of the Nation-State. We believe that this ‘bewilderment’ of finding adequate strategies of overcoming the capitalist crisis is reflected in the bosses’ side. They still haven’t found a restructuring plan that will help them to return in the golden age of capitalism: the post-war years of growth, when their profitability was accompanied by the consent of a big part of working class to the policies applied.

Let’s state it explicitly so as not to create misunderstandings: we do not support the emergence of a new “humanitarian state” model as an attempt of planned overcoming the capitalist crisis from the side of the bosses. We do not construct a linear route from a “State-in-crisis” to the “State-plan”, with the “humanitarian state” as a key point. The restructurings analysed here are related directly with what we continue to label as a “state of emergency”. We support the view that the State tries to build a new ideological narrative for the populations of the exploited (both domestic and foreign) that are thrown to the margins of society in the process of capitalistic exploitation. This narrative justifies the degradation and marginalization of large segments of the modern proletariat through a terminology of humanitarian problem-solving and management. Upon this well-structured narrative, there is a new intermediate layer built between public and private sector; that is the social/humanitarian economy where NGOs are the main actors and a test tube for greater restructuring policies in the capital-labor relation.

On a second level, we can distinguish some political tendencies that acquire a more permanent operating feature within the fluid environment of the crisis. We refer to strategic choices of Capital that have been an answer to the social antagonism of previous decades. Choices, that may not solve all current contradictions of the system, yet they define very clearly what should not happen. One such choice is the reform of social reproduction policies of the working class and their replacement with policies of managing surplus populations. The State neither can nor wants to return to the social-democratic utopias of full-time employment policies and a strong buying power for large parts of the population. It doesn’t want this because this recipe for a welfare state, originally a tool of profitably managing labour-power, ended up offering the exploited the ability to cover needs that historically turned out to be non-productive for the State or Capital through acknowledging worker’s rights and subsidies. But the depreciation of the previous model doesn’t mean the State quits managing the reproduction of labour-power because it needs to secure its discipline and the profitability of Capital. One strategic choice of the Greek capital nowadays is to force the transfer the welfare needs of the workers/unemployed/refugees/immigrants from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Employment to a new regime of “humanitarian” management of surplus populations.

We do not in any case support any idea of a “plan against the crisis” passing through the creation of a “humanitarian state”. We simply say that devaluation of the exploited, as well as their discipline and division are all parts of the bosses’ strategy. It is in this same strategy that the “humanitarian management” plays a part, regarding all those in the “bottom of the barrel”. It’s important here to avoid confusion between the strategical choices of the capital and the tactical moves of those governing. Terms as “humanitarianism” and “solidarity” are at the end of the day nothing but words that SYRIZA uses to avoid losing all their disappointed left supporters. Practically speaking, the measures applied are the same that the previous governments started applying and the next wonderments will continue 9.

A further point, probably more difficult to grasp in its scale and importance, is the multinational change of the class composition in Greece 10) It is not the first time that massive immigration fluxes appear in Greece. It isn’t the first time neither that these immigrants have to face the – state organized – racism of portions of the Greek society. This time though there are some notable qualitative differences. The Greek state did not treat the immigrants from Syria, Asia and Africa the same way as the ones coming from the eastern block in the 90s. In the 90s immigrants were treated as a devalued workforce which would help economic growth. Because of the crisis it nowadays treats them more as a part of a common european problem, using them as an opportunity to absorb money from the EU, and as a means of pressure towards the creditors 11. One more difference is that the immigrants themselves don’t come here anymore with the “dream” to find a 200-500 euro job and build a future in the wrecks of the crisis. They are just trying to get away from war, dictatorships and famine. They want papers in order to travel to the richer north where they can see the possibility of a better life.

Finally, the Greek society itself is definitely in a different situation than in the 90s. An important part of the youth (mostly specialized professionals) try to take advantage of the EU agreements and escape to the north as well. Furthermore, those Greeks who see the immigrants as a threat for their status have changed their hate rhetorics from the common slogan “they are stealing our jobs”. Racist discourses become more similar to the ones we find in other European countries: superiority of the European civilization which is under attack and is threatened by “islamisation” 12. We should notice here that this new tendency of “cultural racism” is a class racism as well. No one accuses a businessman coming from the Emirates to buy a port or an airport… The talk of islamisation, when it came to immigrant children going to school changed to that of a perceived threat to public health. Thankfully in this case we saw antiracist reflexes winning ground.

To sum up, even though there is not grand plan of overcomming the crisis from the part of the bosses, there is central importance attached to the treatment of “surplus population needing humanitarian treatment”. We also consider as crucial the political importance of the race issue in the new class composition which is being formed. While analyzing the agenda of the Greek state and the tactical moves of the left-right governing parties, we consider that the “humanitarian measures” will be kept in the hands of the bosses for some time to come as a useful weapon without implying here that these policies can not be combined with a more direct repression of class antagonism.

In this context of capitalistic restructuring within the fluid political environment of the crisis we seek the potential for linking the struggles of local/immigrant workers in the “humanitarian sector”/NGOs and the local/immigrant “claimants”. It’s not the first time that we are referring to the crucial importance of linking worker’s struggles in public services with the rest of the exploited who are using these services 13. Ιn the cases where such a link was made, our struggles were strengthened to such an extent that they managed to overcome the objective divisions of capitalist social relations, a fact that of course terrifies the bosses for its political implications and possibilities. For a number of reasons, we attribute a strategic importance in linking struggles between welfare industry/NGOs and “claimants” who are using these services.

First of all – although this is rarely discussed in politicised circles – there are many of activists who have or will be employed in some of these positions. A big part of workers in welfare services/NGOs is chosen among graduates of the humanities or the social sciences, who usually have quite some experiences of activism in their student years. On the other hand, due to widespread unemployment and poverty, coupled with the “humanitarian” policies, there are some parts of our class that see the future of the “claimant” ahead of them. Indeed, it is remarkable that people who now are working for the humanitarian sector may be at the same time be both employees and the “claimants”: An unemployed person applying to work through workfare programs at hot-spots is at the same time a “claimant”. Their (forced) work is considered a kind of welfare benefit that enable her/him to survive for eight months, while at the same time his/her job is to serve the housing needs of immigrants.

It is within this social context that, we repeat, the goal of overcoming racial segregation is of central political importance. Restructuring of the welfare systems through forced work in workfare programs has been introduced for the first time for local unemployed and we see it as a key factor in the future management of migrant populations. On the other hand, the “humanitarian” approach to the needs of immigrants, where basic social benefits are combined with measures of deprivation of liberty, social exclusion and control, is also a picture of the dark future which is in store for the local proletarians.

This objective class condition generates struggles with similar content that remain separated on the basis of racial privilege. For example, the state’s choice to keep refugees/immigrants separate from the fabric of the society, generates refugee/immigrant struggles against social exclusion and for freedom of movement, due to the many road accidents in the desolate outdoor environment of hot-spots. At the same time, this condition of isolation forces many local “claimants” to need to travel many hours each day to go to their eight-month temporary work, while at the same time facing the deadly threat of a road accident. After such an “accident” in the hot-spot of VIAL (Chios Island), although we saw the “public service” workers complaining (as they should do) about their working conditions and demanding safe and free transportation at their workplace, we didn’t see any reference to the corresponding “accidents” happening to the immigrants for the same reasons. Let us just ask how stronger would be the struggles of the “public service” workers if they had the support of the immigrants and, accordingly, how much more powerful might the riots of the immigrants be after some deadly traffic “accident” if they were accompanied by “public service” workers strikes… Let’s just hope that the possibility of the linking of struggles between native-immigrants will not just be the product of our vivid political imagination… What we know with certainty is that small everyday struggles break out on both sides and that although they remain, most of the times, invisible for the activists of the radical movement, the state is taking them seriously and represses them directly. This is the case, for example, of workers in asylum services, who went against their political superiors, prevented the expulsion of several immigrants, by not recognizing a “safe country” status in Turkey 14.

We have seen above why work in the “humanitarian” field of the state and in the NGOs is of particular importance for the ongoing capitalist restructuring and therefore becomes crucial for the linking of our struggles. The other half of such an analysis, regarding struggles against the “humanitarian” and immigration policy of the Greek state, concerns structures that have been created by the movement over the past two years, aiming to cover directly the basic needs of refugees/migrants, mainly in the form of squatting empty buildings. A key starting point must be the historical assessment and perspective of these structures of the radical movement. In previous years, we were among those who criticized the attitude of several anarchist/authoritarian/autonomous groups that were speaking about proletarian immigrants through posters, demos etc., where the subjects themselves were almost never involved. In the case of immigrant squats, we see that for the first time a part of the radical movement embracing structures that have as first political priority to cover the immediate material needs of immigrants themselves, through the active participation of them. At the same time, it is a historical turning point regarding squatting in Greece, where, unlike Western Europe, the squats were mostly places of anti-culture or political discussion of radical youth, rather than trying seriously to focus on the housing needs of local proletarians.

Besides an indication of the coming of age of the anarchist/anti-authoritarian milieu in Greece, the immigrant’s squats are also an important battleground against the policy of social isolation, detention and deprivation of freedom of refugees/immigrants. For this reason, we see the state changing its policies towards squats. At first, SYRIZA showed a relative tolerance towards the immigrant’s squats, which is explained by taking into account two factors. Firstly, the fact that SYRIZA himself as a historical product of class struggle is linked to the struggles for the rights of immigrants and so it will implement policies that also aim to satisfy those from its electoral base who are still “sensitive” in “progressive topics”. Obviously, this would not concern an exclusively right-wing government, who, for the same reasons, would choose serving the Church and its conservative constituency as a first priority. Secondly, since, as we have seen, the “refugee crisis” erupted under the SYRIZA-ANEL government without any organized plan to deal with the magnitude of the issue, the housing squats of the immigrants and self-organized aid structures at refugee camps gave a “radical edge” to the policy of the Greek state, which doesn’t want to expend funds for covering the immediate needs of migrants.

This policy of tolerance seemed to change after the EU-Turkey agreement and the evacuation of the refugee settlements in Idomeni, Piraeus, Victoria square etc., which was followed by the targeted evacuations of some immigrant squats. No matter what some SYRIZA voters believe, the state under the SYRIZA-ANEL government deals with squatting as a direct conflict with the bourgeois state itself, which safeguards the “sacred” right to private property. Furthermore, the repressive shift of the “first-ever left government” can be explained by the need to control and put some limits at the movements of the immigrants in order not to hinder the policy agreed upon in the EU-Turkey agreement. For this reason, the state under the SYRIZA-ANEL government chose the “intelligent repression” of squatting, by evicting squats that were NGO properties. The propaganda that came together with the evictions was that the squatters are “hobbyist solidarians” who come largely from western Europe and create problems. SYRIZA also chose to hit simultaneously Villa Zografou (a squat of the antiauthoritanian milieu) and Alkiviadou squat, where immigrants lived. They did this knowing (from their “radical background”) that the attention of the anarchists/antiauthoritanians would be turned mostly towards their own squat, rather than an immigrant’s squat like Alkiviadou...

Of course, referring to the “intelligent repression” of the government, it is necessary not to overestimate the dynamics of such solidarity structures of the movement in comparison to the size of the migrant population. For sure, the number of migrants who will be able to get involved in such structures can’t be compared to the number of immigrants who will find themselves in detention centers of the state. Even so, we must accept that it’s much better to live in a squat than being in a detention center/hotspot. Nethertheless, it’s more important to accept that self-organization is not the “key that opens all doors”, especially in the refugee/immigrants issue. Τhe truth remains that the movement can’t cover the vast needs presented to it. What it can do is to bring these needs in the first line and try to create multi-ethnic communities of struggle, which can try satisfying these needs both through solidarity structures and struggles of demands voiced towards the state.

A prerequisite for trying the second is the struggle for the political recognition and visibility of immigrants through the demand for “papers for all” and for equal political/labor rights with Greek citizens. The central importance of this struggle has been underestimated by many anarchists, since it is considered to be a “reformist” demand for rights from the bourgeois state and thus it is integrating our struggles into the state. Obviously such demands don’t fit with the analysis that self-organization is the “key that opens all doors” against the capitalist restructuring. On the other hand, for us demanding papers for all refugees/migrants is of great importance because, first of all, it is the first thing the migrant subjects themselves will seek. Furthermore, the struggle for papers has to do with overcoming the fear of being arrested of harassed every time one goes out in the streets, just because he or she was born in another part of the planet.

Assembly for the Circulation of Struggles

skya.espiv.net

Notes:

1 A catch-all term used by SYRIZA politicians to eschew emotionally charged words like “creditors” or “lenders”.

2 For the analysis of our collective you can check the text “The SYRIZA-ANEL government, the cycle of struggles against austerity and the future of social antagonism”: https://skya.espiv.net/2016/10/25/syriza-anel-government/ .

3 The basic income/“social solidarity benefit” (KEA) is a bonus income of €100-400 per month for households that are living below the poverty line. It also replaces other welfare benefits (i.e. rent allowance, free electricity, etc). The “claimants” have to accept any job proposed to them by the Unemployment Office, as well as accept periodic checks in their households that aim to establish whether they receive undeclared benefits or have other means of making a living.

4 “The Austrian Foreign Minister Kurtz sugests “forced labor for those who are entitled to asylum and have no chances in the labor market”, see https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/1657133/migrants-in-austria-will-be-given-jobs-paying-just-e1-an-hour-until-they-learn-to-speak-german-or-have-their-benefits-slashed/

5 This tentative licentiousness seems to be running out at the time of writing of this text, with the evacuation of the housing squat of Alcibiadou street in Athens, and “Albatros” in Thessaloniki in the spring of 2017. There were also the evacuations of squats in Thessaloniki in the summer of 2016.

6 A very interesting analysis of the NGO phenomenon is included in the brochure “humanitarianism without borders, but with fences” of the musaferat collectivity in Lesvos, Greece. https://musaferat.espivblogs.net/en/

7 We should note here that this devalues the contestation movement of immigrant subjects in their country of origin, as well as when they effectively cancel fences and borders in the West – they are thus treated as powerless victims of international geopolitics. A characteristic example is the negative attitude of a big part of the anti-authoritarian/anarchist/autonomous milieu towards the popular uprising against Assad in Syria in 2011, which formed part of the “Arab spring”. Perhaps this negative position is an offspring of the links of the Syrian dictator to Putin’s Russia, which some have come to consider a friendly force in their anti-imperialist analysis.

8 Of course any wage relationship does not absolve workers from the choices they have made. Someone working in guarding people that have not committed any crime whatsoever is in no way absolved of his or her responsibility for perpetuating power and racist relations. We make a note here, however, that this is mostly the job of the police and army, and not of the NGOS, so lumping them all together as in most radical analyses does not help to establish the amount of responsibility for workers in NGOs. We recognize the many issues posed by the work in NGOs, but also the gap in the analysis of such issues.

9 Like the basic income, which was at fist implemented by the coalition of neoliberal with social democrats, then was renamed by SYRIZA as “social solidarity benefit” (KEA) and we are sure that will be implemented by the next governments, no matter the given name. On the KEA benefit, see also note 3.

10 We are using the notion of “class composition” in the broad sense of the exploited class, without meaning specifically the direct relation of the immigrants with the production process. Of course we acknowledge that some immigrants have bourgeois and petite-bourgeois origins. We keep in our minds the fact that because of their current condition, the immigrants closed in camps can not even be considered as unemployed. They form a population in a grey zone, cut off from the official labor market. But this gray zone is not cut off from the total valorisation process of the capital. In marxist terms, they are currently becoming from subject of the production process an object of the same process through which humanities and social science graduates find a job, the NGO’s get money and the capitalist restructuring advances. So, we use this term in a “non-workerist” way because of the future that we suspect as planned for them. A future as part of a vast tank of claimants fitting in the European plans for labor market reforms. We certainly know that it is too early to make any prediction for their future, which for now seems to contain a lot of imprisonment, but we find the scenario described above quite probable.

11 See also for example the unilateral action of the greek government in Christmas of 2016 not to increase VAT on the islands of the eastern Aegean, where are operating detention centers for immigrants.

12 However, in the most serious social battle against the racism of parts of Greek society, for the right of access of refugee’s children to schools, racists didn’t use directly the argument about islamization. Among a general dealuative condition in the educational system, they argued that immigrants are a “health threat”, using the ignorance of many locals about these issues, and the fear that they will lose their privileges. On the other hand, in this battle, we saw on several occasions the anti-racist arguments having a strong presence, something that doesn’t confirm the generalization of “diffuse racism of Greek society”. This issue, of course, requires a separate analysis that goes beyond the aims of the text you are reading.

13 Especially in health industry or in public transportation, for which we have written some collective/personal texts in Sfika, the journal published by SKYA.

14 Most of these workers were fired after a period of time and replaced by servants directly controlled by the state. For this case there is a text written in our magazine.

Griekenland: kapitalistische herstructurering onder de regering Syriza-Anel – https://arbeidersstemmen.wordpress.com/2018/10/08/griekenland-kapitalistische-herstructurering-onder-de-regering-syriza-anel/